The making of a platform

I got inspired by Flipper Zero and started developing an application platform for ESP32 touchscreen devices.

Prologue

Some time in mid-December, I was wondering if I should buy a Flipper Zero device. The official website describes it as follows:

Flipper Zero is a portable multi-tool for pentesters and geeks in a toy-like body. It loves hacking digital stuff, such as radio protocols, access control systems, hardware, and more. It’s fully open-source and customizable, so you can extend it in whatever way you like.

I’ll refer to F0 instead of Flipper Zero in the text below.

F0 allows you to play around with technologies such as BlueTooth, USB, infrared, NFC and much more. It offers a neat software development platform so you can easily output graphics and communicate with peripherals. It also has a cute dolphin pet that levels up as you explore. Its software is very interesting and I found myself wondering whether I could port the code to another microcontroller (MCU).

ESP32 has been my favourite MCU for the past few years. Most variants of the hardware come with a multi-core 240 MHz CPU, WiFi, bluetooth, 520kB of RAM (expandable to 8MB), several megabytes of storage and a bunch of wired connectivity options. It’s roughly the size of a postage stamp (18 x 25.5 x 3.1 mm) and it costs about 2 EUR before adding a USB port and a battery to it. For those who are interested: Flipper uses an STM32WB55 MCU.

My porting efforts didn’t start out smoothly, but one thing led to another and 3 completely separate iterations later, I’ve got something that looks usable. The result is an application platform called Tactility.

Originally, I intended to port the F0 project partially to ESP32 with as little deviation from the original as possible. I first started with copying a ton of code and removing the bits that weren’t needed (yet) or that were blatantly incompatible. This was not a successful approach: once everything compiled, it was too hard to debug memory corruption issues.

In a second attempt to make a Flipper-like platform, I tried to make everything from scratch. It didn’t take long for me to realise that it was way too much work and I found myself copying in more and more bits from the Flipper project.

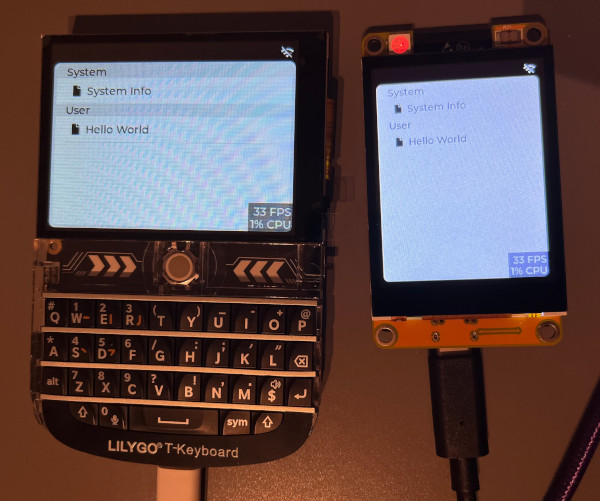

In my third and final attempt, I did something in-between: I started building up the platform with mostly existing F0 code. The main difference was that I was importing smaller bits and verifying them before moving on to the next feature. I also wasn’t afraid to implement certain things radically different if it was beneficial to the project. This worked better and I soon had a functional prototype. It featured an application launcher and the ability to start and quit applications:

Making the app makes the platform

Let’s dive into the software development journey…

It didn’t take long to build a few simple apps like “Hello world” and one that showed memory information. I also had a ‘desktop’ app at this point, but this wasn’t very challenging as it just lists the installed applications and launches them when you click on them.

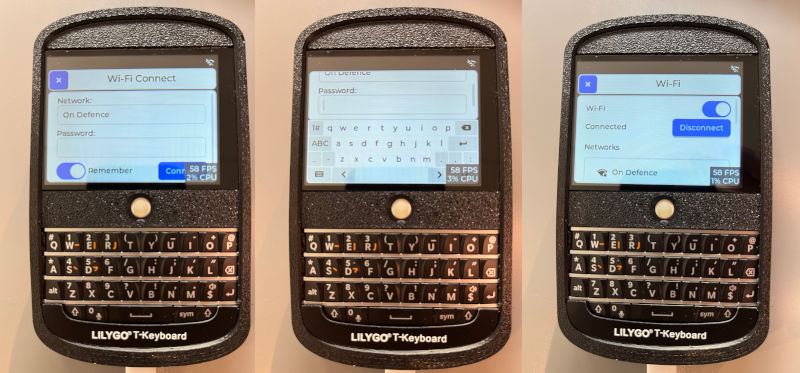

When I set out to make a Wi-Fi service and related app, I didn’t know just how much it would change the entire platform! A good Wi-Fi app does a lot more things than you’d expect. Not only is it multi-threaded, you also need to store settings. And then there’s the increased complexity in UI and user experience.

As I was making this feature, it resulted in a complete change of the platform. I started with a simple screen to toggle Wi-Fi on/off. So far so good. Then I needed an additional screen so the user can enter credentials to connect to a network. This almost doubled the amount of code and suddenly the app had to manage “which screen should I show - and when?”.

I decided to split the Wi-Fi app into two separate apps: one for the Wi-Fi overview and one for connecting to a new network. To implement this, I now had to support:

- Launching an app from another app, and being able to return to the original one.

- Launching an app with parameters, because I wanted to have the SSID field pre-filled when you pressed on it in the Wi-Fi overview.

- Storing the Wi-Fi credentials.

- … securely, so I had to implement encryption/decryption …

- … and I had to find a way to store the decryption keys in a safe (enough) manner.

What’s in an app?

Similar to Android and Flipper Zero, I created a ledger that defines a user app. It looks like this:

static void app_show(App app, lv_obj_t* parent) {

lv_obj_t* label = lv_label_create(parent);

lv_label_set_text(label, "Hello, world!");

}

const AppManifest hello_world_app = {

.id = "helloworld",

.name = "Hello World",

.icon = NULL,

.type = AppTypeUser,

.on_start = NULL,

.on_stop = NULL,

.on_show = &app_show,

.on_hide = NULL

};

This is a functional app. It shows the text label on the screen and nothing more. It almost looks like object-oriented programming. In fact, I might create a C++ wrapper in the future.

Background services work in a similar manner.

The main difference is that they don’t define on_show, on_hide, an icon or a human-readable name.

App lifecycle

When you have apps starting other apps, you can consider it as a stack, which you aproach as LIFO or “Last In, First Out”: The last app that is put on the stack is the one that is shown to the user. It is also the first one to be closed before you can get back to the app that was launched before it.

Starting an app and closing goes like this:

- Create the app (allocate data)

- Create the views (UI) for the app and show them

- Hide the app and destroy the views

- Destroy the app (free up data)

When app A starts app B, then the views of app A would be destroyed as the app is hidden, but app A itself would not be destroyed. When app B is closed and destroyed, the views of app A would be re-created and shown again.

Once I was able to launch apps onto a stack, I wanted to be able to launch them with certain parameters. Flipper Zero originally just passed a string, but I wasn’t a fan of that: command line arguments are terrible to process. Instead, I opted to use “bundles” like on Android. A bundle is a sort of flexible dictionary that maps strings onto a specific set of types. It’s a simplified in-memory database (key-value store) with a flexible type system, while still using explicit typing.

This is how bundles work on Tactility:

// Make a bundle and store some data in it

Bundle bundle = tt_bundle_alloc();

tt_bundle_put_bool(bundle, "is_enabled", true);

tt_bundle_put_int(bundle, "count", 42);

tt_bundle_put_string(bundle, "label", "Hello, world!");

// Check if the key and value exist...

int value;

if (tt_bundle_opt_bool(bundle, "some_key", &value)) {

// ...

}

// This one crashes if the key doesn't exist:

bool is_enabled = tt_bundle_get_bool(bundle, "is_enabled");

Security and risk

Typing the Wi-Fi password on a touchscreen was becoming tedious. It was happening after every reboot. That’s why I needed to store the Wi-Fi credentials on the device. Once encrypting and decrypting was working, I still wasn’t done. The problem with encryption is that you need to store the secret that decodes the encrypted data. You can ask the user every time for a password to decrypt, but then you’ve got yourself the same problem as when entering the Wi-Fi password manually: that’s tedious!

The most simple way to approach this, is to create a reasonably safe random set of numbers as the key, and store that key somewhere safe. This approach is not safe if an attacker has physical access to your device: they can connect via USB and fetch all the data from the flash memory (all the partitions on disk). This holds the encryption key and the encrypted data.

This was pretty bad, but the solution was fairly obvious: enable boot protection and flash encryption. The problem with these features is that they are not easy to set up. Most hobby developers won’t bother. So, instead, I opted to show a warning when a credential is stored on an unprotected ESP32.

It didn’t sit right with me. I knew most hobby devs won’t bother with setting up these security features. I knew there wasn’t much I could do to make it safe, but I found a way to make it better: If I can use some kind of secret information that isn’t readable from flash, but also isn’t easily available via the USB interface, perhaps I can mix this into the cryptographic key?

That’s where the eFuses come in: An eFuse is a programmatic fuse. You can blow the fuse once with software, and that’s it. Each fuse can be seen as a single bit of data, so if you have enough fuses, you can create a storage mechanism.

The ESP32’s eFuses already offer 6-8 bytes of random data. There is more data space, but it’s all set to 0 by default. With the hardware identifier, I could now create the private key as follows:

- Make a buffer with 32 bytes and fill it with random data (in a safe manner with a seed).

- Make another 32 byte buffer and fill it with the repeating hardware identifier.

- Perform a binary XOR operation to combine both buffers.

An attack wouldn’t be as simple as just copying the data over USB. An attacker that wants to remain unseen would have to:

- Copy all the flash data (complete backup)

- Upload a malicious app to fetch the eFuse data

- Re-flash the original data

It’s not a lot more secure this way, but it sure takes a whole lot more effort. I’ll still keep showing warnings when secure boot and flash encryption aren’t enabled though.

What’s next?

I’m still working on UI/UX improvements for the Wi-Fi app. The connection dialog doesn’t have a “busy” animation as it connects. At a later stage, I also want to have Wi-Fi auto-reconnect and have the option to have Wi-Fi enabled (and connecting) on boot.

Right now, I’m looking at writing some tests…